These posts contain my long-form thoughts on what’s going on in my world.

Learning Styles are a Myth

tl;dr:

learning styles are a myth - it’s a bad way of thinking about individualized learning

What we need instead is a better understanding of the learner, and in particular, what they already know so that we can match them with the appropriate level of difficulty for their capacity. That involves creating scaffolded learning experiences that start with narrated examples and moves towards independent practice.

Here’s the argument:

In order for learning styles to be true, an experiment needs to validate their existence. This is what the experiment would look like (adapted from Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence)

Learners:

state their desired learning style (Vistual, Auditory, Reading, Kinaesthetic)

are grouped according to their learning style

are taught in accordance with their learning style

are assessed using a learning style agnostic test

are then taught and assessed using their non-preferred learning style

The results from the first test (4) must outperform the results from the second test (5). Because of the lack of evidence for the claim that learning styles exist, the authors conclude “at present, there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning styles assessments into general educational practice.” Other authors have come to the same conclusion. So the methodology that would need to be followed in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of learning styles does not exist. Why, then, is the idea of learning styles so pervasive?

There is an intuitive appeal to the idea of learning styles. For example, someone recently was telling me that she prefers a book (reading) because sitting and listening to a lecture (auditory) does not work effectively for her. She sees that it works well for others, but not for her. Likewise, some people claim that they need to talk through (auditory) the information in order to make sense of the information. In both of these situations, there is a misunderstanding of what is happening during the learning process. In order to learn and retain information, that information needs to be made meaningful by being related back to previous experiences. For example, someone during a lecture might be talking about managing addisonian crises. Someone who is a novice learner will likely need to take their own time and work through the specific details of the case (look up reference material, learn the mechanism of action, etc.) whereas someone who is an advanced learner might quickly understand what the crisis is and is only looking for the information on how to manage the case. The novice learner will then have a hard time following the lecture whereas the advanced learner, having sufficient background information to relate the case to, will only need a few words in order to advance their own learning. In sum, it’s not the style of learning that determines acquisition and retention of information, but it is the match between the learner and the complexity of material that is a better determinant of the learner’s success.

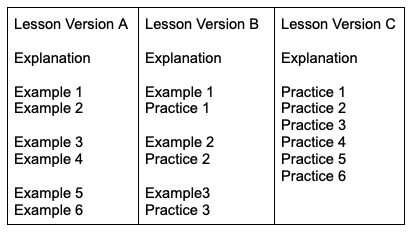

What is the alternative to learning styles? In principle, the idea of tailoring the information to the needs of the learner is a good one. What is not good is using learning styles as the framework for determining how material should be presented. An alternative, and one that is more in line with the literature on learning, seeks to categorize the material based on a spectrum from novice and simple to advanced and complex. For novice learners, using worked examples is best. A worked example is “a demonstration that illustrates a specific sequence of the steps to complete a task or solve a problem.” (Clark, 208) What starts with demonstration, ends with practicing. In each succeeding lesson, the learner takes on a more active role in the learning. Here’s how Clark visualizes this process:

The learning experience is scaffolded for the individual. This kind of scaffolding works really well for skill acquisition, such as problem solving, or manual skills such as surgery or mechanical repairs.

This kind of learning relies on inductive inferences: extrapolating from many instances to general principles and abilities. This is a more effective way of learning than deductive inferences: learning the general principle and trying to figure out the context for that principle. In the first, the guesswork is taken out of the situation because the learner is working through the individual situation to create the principle that should be applied in the future, and so understanding when it should be applied has already been practiced. Whereas with deductive learning, the individual learns principles but doesn’t know precisely where/when that information should be applied. This introduces a level of extraneous cognitive load that is unnecessary for the learner.

References:

Clark R. & Safari an O'Reilly Media Company. (2019). Evidence-based training methods (3rd ed.). Association for Talent Development. Retrieved November 3 2022 from https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/-/9781949036589/?ar.

Coffield, F, Moseley, D, Hall, E & Ecclestone, K 2004, Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: a systematic and critical review, Learning & Skills Research Centre, London.

Kirschner, P. A., & van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2013). Do learners really know best? Urban legends in education. Educational Psychologist, 48(3),169e183. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.804395.

Kirschner, P.A. 2017. “Stop propagating the learning styles myth.” Computers and Education, 106, 166-171

Pashler, Harold & Mcdaniel, Mark & Rohrer, Doug & Bjork, Robert. (2008). Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 9. 105-119. 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x.

Critical Review of Dolby’s Learning Animals

A critical review of Nadine Dolby’s Learning Animals

The following is a critical summary and response to Nadine Dolby’s Learning Animals: Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Becoming a Veterinarian

As someone who studies philosophy, I am interested in the argument that someone makes and the evidence that they use to support that argument. From that perspective, here is the argument that Dolby makes:

Veterinarians are held up as society’s teacher’s of animals

Veterinarians are not taught to see the whole animal

Therefore society’s view of the animal is incomplete

The way that Dolby constructs this argument is through utilizing frameworks by authors such as Pederson in order show this transition into becoming a veterinarian as a deliberate attempt to erase the sentimentality towards animals:

[McInerney’s] defense of dissection reinforces Solot and Arluke’s (1997) argument that the overarching objective of dissection is not the learning outcomes of cutting open a dead pig to learn about pig biology (and its similarities to human biology) but to be able to replace the sentimentality of childhood feelings toward animals with the detachment of emerging adulthood.(16)

Through veterinary education, students are not asked the hard questions about our relationships with animals, and as such, those students themselves have a fraught relationship with animals that manifests itself as trauma that is not adequately addressed by the educational system.

That is a compelling argument and one that offers an explanation for the emotional distress that many, if not most, students in veterinary medicine face today. In the abstract, it just seems to make sense. But as I wrote at the beginning of this, I am looking at this from a perspective that forces me to ask about the nature of the claim and the evidence used to support that claim. Here is where we start to look at the methodology that Dolby uses: she interviewed 20 students from one veterinary school one time per year over the course of their four year veterinary education. That’s 4 days per student out of 1,460 days of their education, or for all the students, that’s 20 days out of 29,200 days. That represents .069% of their veterinary experience. From another perspective, there are 20 students out of a total of anywhere between 13,000 and 14,000 veterinary students in veterinary education at any one time. So those 20 students represent 0.15% of the total student body. A generally accepted standard is in order to get a representative sample is 10%. Without showing us the math, Dolby outlines her approach here:

I use their stories as the basis for this book to map what happens to these students from the early days of veterinary school to graduation. I reflect on and analyze how their experiences during this period shaped their beliefs and perspectives about animals, their relationship with animals, their views on animal ethics and animal welfare, and their views on the veterinary profession. Through their narratives I write the story of how our society’s primary teachers about animals are schooled: what they learn and do and what is absent, hidden, or simply ignored (6)

From this, we can see that generalizing to an entire student body from the accounts of 20 students is sloppy at best, unless of course there is another agenda at work.

Dolby writes about the “disappearance” of the animal: “Thus, the story, and the through-line, that I expand on in the remainder of this book is one that slopes toward disconnection and eventually, the total disappearance of the animal.” (37) without explaining exactly what this disappearance means. Taken as a hyperbolic statement, we can then back that statement down to see that Dolby is saying that, with some of the previous quotes throughout the book, that veterinary education ignores the sentimental relationship that veterinary students could have with their animals.

There are times when Dolby will make statements like the following that help us to see the background that she is operating from:

Strong emotion was a constant part of these conversations, both for the students and often for me, as I struggled to hear and respect the students, their stories, and realities, while at the same time often vehemently disagreeing with their positions on animal welfare and rights. (27)

From this perspective, a different argument takes form. Dolby claims that she is examining veterinary education from a critical pedagogy lens, but there are times throughout the book when she articulates a different background: one of animal welfare and rights. She doesn’t explain this perspective other than using words like “torture” (44) and “suffering” (22, 119, 136) to describe the activities of the veterinarians on the animals. A different agenda starts to become apparent: veterinary education, through its intentional exclusion of non-clinical relationships with animals, forces veterinary students to suppress their sentimental relationship with animals. This sentimentality would see the inherent violence towards animals that is part of the educational system, but instead it is suppressed and that suppression is reaffirmed and reinforced by educators and peers in veterinary education. Were veterinary students not forced to bury their feelings about the torture of the animals, then those students would not experience the trauma and irreconciliability of their oath to do no harm and the harm that they cause the animals. Thus one student in particular is left “to rediscover her own humanity within a system that tries to deny it.” (91) It seems, then, that Dolby is doing more than just saying that educational reform needs to happen, she is saying that veterinary students are torturing animals and causing needless suffering for those animals. That animal suffering then in turn is causing the students to suffer because they are denying their inherent sentimental relationship towards animals. When we look at the evidence that Dolby offers to make these claims, it becomes abundantly clear that she does not have sufficient evidence for the claims. It appears, then, once we see the background of animal welfare and animal rights that Dolby is arguing from, then we see that she is using the students in order to further her own agenda of reforming education without doing the requisite work of explaining just how the actions of the students amount to torturing the animals.

What I’m left with, as someone who was incredibly excited about a critical appraisal of veterinary education, is a book a study that takes advantage of the vulnerabilities of veterinary students in order to further an animal rights and welfare agenda and make claims about the psychological states of those students without sufficient justification. Everyone in veterinary medicine, whether directly involved with the educational system or not, everyone knows that there are wellbeing issues (take, for example, all of the work that Merck does with its wellbeing studies). What we don’t need in veterinary medicine is someone coming into the space under the auspices of a detached, pedagogical perspective who is only trying to further their own agenda and utilizing veterinary students as the prop to support that agenda. We need real change and real reform and it’s not going to come from Dolby’s Learning Animals.

I got fired. Now what.

Ok, that title isn’t entirely true. I’m not even sure if I was fired. I know that I had a job, then I had a conversation with the CEO and the head of Human Resources, and at the end of it, I didn’t have a job. I know that I didn’t quit. There doesn’t seem to be a third option, so I need to conclude that I was fired. You, reader, might be confused. It seems pretty straightforward: if you don’t have a job and you didn’t quit, then the conclusion must be that you were fired. Here’s why I’m confused.

There wasn’t a violation of company policy. I didn’t swear at a customer or tell the President to go fu*k himself. I didn’t get into a fight or steal company secrets. I wasn’t drunk on the job. You could almost count some of those recruiting events as being “on the job” but I was never drunk.

I didn’t fail to perform my duties. At least, I don’t think I did. To be honest, I never really understood what my job was. And by that, I mean that there weren’t any particular KPIs or targets that I was supposed to hit. It’s not like I had X of students to get through Y of programs. It was sort of like, “hey, come join the team. We’ll figure it out when you get here.”

I wasn’t the wrong cultural fit. When I was hired, we were in the middle of a headquarters hiring frenzy. The mantra was “hire great people and we’ll find a place for them when they get here.” This can be a great hiring tactic if you’ve got a lot of vacant seats and you need to fill those seats with great people. But this only really functions well when you have role-assigned seating and you’re looking for people to fill those roles. Otherwise you’re more likely to end up with a great party than a great company.

I did get some feedback during the firing conversation. There was a comment about not being able “get it done” and that, when someone recently gave me feedback, I reacted negatively. When I asked for more details, it was clear that the conversation was more about what the next steps looked like than it was about finding out the reasons why I was being fired.

Getting fired was definitely a shock. I had a choice: I could either fight it, culturally, socially, legally, or I could accept what it was and move on. The CEO was generous with the severance package and was also willing to financially support my green card application, so I wasn’t at all inclined to take the legal route. Instead, I took the latter and I decided to move on.

The reasons why I took that second choice, I think, had to do with what I did directly after being fired. First thought: call the wife. I texted but she was at work and unable to get the phone. So I texted a friend and asked him if he had a minute. He called me back almost right away. I told him what happened and he wasn’t impressed. Then he said something that I’ll never forget, he said “Ok, over the next little while, a lot of thoughts will be running through your mind. And a lot of those thoughts will be negative. But there’s one thing that you have to know: you are surrounded by people who love and care about you and they’ll do anything they can to help you through this.” My eyes welled up when I heard those words and my eyes continue to get misty when I think about them.

There are moments in life when the right words appear at the right time. Back when I was 18 and I had just been turkey-dumped (for those of you who don’t know what a turkey dump is, it occurs at thanksgiving every year when freshmen and freshwomen return home from college and break up with their significant other - who likely stayed home to wait for them while they went to school) by my first real girlfriend. We had talked about marriage. I gave her a promise ring. I know. Total cliche. I was devastated. I quickly spun into a downward spiral of depression. I buried myself in philosophy, looking for answers about how to deal with all of those negative emotions. And I eventually found what I was looking for. In the midst of the beginning stages of that spiral, my father and I had one of those right-words, right-time conversation. He simply said “Aaron, I really liked her. But she hurt you and I can’t forgive her for that.” It was a simple truth that I don’t think I was willing to accept at that moment, but those words have stuck with me since then. The simplicity of undeniable truth that comes from a place of love is sometimes the most important thing that we forget to say.

Back to the moments after being fired. I wiped the mist out of my eyes and I knew that I needed to get on my bike. Cycling has always been therapeutic for me. Whatever I was dealing with, by the time I got to the top of the first hill or around the first set of technical obstacles, whatever it was, it was always a little less potent. Usually by the time that I get home, it was gone. With each pedal stroke, I’m able to push the pain and frustration through my legs, into the pedals, chain, wheel and tire, inevitably leaving it on the tarmac or buried in the dirt behind me. That works most of the time. This time was special. There would be no forgetting this time.

I took one of my regular routes around Dixon reservoir. Just hilly and technical enough to force me to be in the moment. As I rounded the furthest turn and started to head home. My phone rang. It was my wife. She was driving home from Denver. I asked her if she had a moment to talk and suggested that she pull over - Denver traffic can be brutal at the best of times, and this was not a conversation that I wanted to have with her on interstate traffic during rush hour. She said she was able to talk, and so I told her. She cried. Luckily for me, by this point in the ride, the endorphins had kicked in and I was able to gather my thoughts enough to say “It’s not great. It’s not what I would have chosen, but we’re going to be ok. We have money saved up for just this kind of situation. We’re going to be alright.”

While we were talking, a friend rode past, heading in the opposite direction. We waved as he passed by. A few minutes later, I was just finishing up with my wife and he came back, now heading in my direction. This particular friend is unlike a lot of other people I know: he’s always upbeat, positive, and always talking about great rides, either upcoming or recently past. Standing there with the shock wearing off, the endorphins coursing through my veins, having had the conversation that I needed to have with my wife, I was able to just be there in the moment with my friend. We talked for maybe 10-15 minutes about some of the great gravel rides in the area. He gave me all sorts of suggestions for places to go and groups to join. In those moments, he was the embodiment of community: warm, welcoming, encouraging. We didn’t talk about my being fired an hour before. We just talked about bikes. We rode together for the next mile or so and then he turned right and I kept going straight as we waved goodbye. This next part may seem strange, but I couldn’t help but think that he was my spirit animal. His overabundance of positivity was exactly what I needed in that moment. Not a wallowing about what pain I must be in or a discussion about the uncertainty of the future. Nope. Just a conversation about the simple joy of riding a bike.

When I got home, friends who were visiting from out of town were there. I told them what happened and they asked if I needed space, if I needed them to get a hotel or something. I told them that wouldn’t be necessary. I talked. I rode. I’m going to be ok. That, in fact, ever since I went through the terrible cliche of the turkey dump, I enjoy moments like this because it gives me a chance to become exactly the person that I want to become: able to create a moment between action and reaction, able to, in that moment, decide how I want to react. And I chose to react with a simple statement: what can I learn from this?

So here’s the “now what” part of the story.

I texted another friend and a couple days later I was spending the night at his house, bellies full of great pizza, and sipping on bourbon. We talked about his experience being let go from a very senior position. It was also a shock to him because there wasn’t a clear reason why it happened. He gave me some advice that nobody had given to him previously: “Take the time. Take the severance and go somewhere that’s been on your bucket list for a while. You’re very unlikely to get this time again, that is, until you retire. So take the time.” Sage advice.

I spent two weeks biking, camping, and staring at the mountains with my dogs down in Buena Vista. Not too long after I was on a week long bikepacking trip across parts of Utah. Then up in Steamboat for more biking. Then to Peru for three weeks, hiking the Andes and walking around the Incan ruins of Machu Picchu. In each of those places, whether by myself or with others, I found simple truths that were undeniable and potent. While staring at snow-capped Mount Princeton, my three dogs passed out at my feet, I realized something that was so obvious that its obviousness belied a deeper meaning: I love my wife and my wife loves me. You would think that after six years of dating and seven years of marriage, that it would be obvious that we loved each other, but there was something else there. It wasn’t just about loving each other, but it was about the support and completeness that I felt when I thought about her. Thinking about her made me feel a deep sense of grateful abundance that took away the fear about what might be and gave me a sense of what can be. I can shape and share the life that I want because of her perpetual support of what I am going to do with my life. I had planned to spend an extra week in Buena Vista, riding and whatnot, but in that moment, while staring off at the collegiate peaks, I knew that I accomplished what I set out to accomplish and I just wanted to be back home with my wife.

In between trips, I was reaching out to people, letting them know that I wasn’t with the company anymore. I wasn’t looking for a job, but just looking for advice - what would they do if they were in my situation? Lots of well-wishing came in that was supportive and helpful, but most of the conversations ended on a slightly surprising note: most people said that normally they would be concerned, but they weren’t at all concerned about me. They knew that I would land on my feet. When I was in the midst of the moment, where the future is uncertain, where I wasn’t sure if and when my next paycheck was going to come in, I thought that I wanted to hear people say that they were worried about me and that they would do whatever they could to help support me. But instead I got a more encouraging note resonating throughout our conversations: I had everything that I needed in order to be successful. I left each of those conversations with a feeling of wholeness that could only have come from the hard simple truths that each of my friends shared with me: I had everything that I needed to be successful. It was just a matter of becoming successful that was up to me.

So I listened. And instead of rushing into the next job, I’ve been thinking more and more about the kind of person that I want to become, which helps me think about the kind of job that I want to have, and further helps me think about the kind of days that I want to live. A thought occurred to me during this process: the only thing that’s not in your control is how much you’re going to get paid. But other than that, you can start to live each day as you would like. I have this belief that if we live how we want and exercise all of our faculties, then the money will come. Focus on solving problems, real problems for real people, which is how I enjoy living my life, and the money will follow. It might not be hedge-fund money, but it’ll be enough to sustain the kind of life that I want.

Here’s what that day looks like. I get up at 5:30 every weekday. I stretch for 10 minutes, meditate for 10 minutes, make myself a tea, then get to work. My “work” right now consists of building up the site that you’re likely reading this on. I write. I reflect. I think about the challenges that I need to overcome. I need to be more organized. I need to underpromise and overdeliver. I need to be less distracted. I keep a journal of what I’m doing at each moment and write down every time that I’m distracted up until around 8am. Keeping track of the entire day is not possible at this point. That might come, but right now I’m trying to create enough of a routine that I will accomplish what I want and I won’t be so easily distracted.

Slowly I’m becoming more focused. The writing is coming back to me. Around 6:30, my wife’s alarm goes off and she requests a snuggle during her 10 minute snooze, to which I am happy to oblige. Then back to work, writing the blog, creating the newsletters. I’m getting better at mapping out what I want to accomplish each morning. Eventually I’ll start keeping an end-of day log to reflect on what went well and what I need to improve on for the next day. The idea is to create as much of a routine as possible, reduce decision making and fatigue, accomplish what I want, and become the person that I want, one routine at a time.

The point is to start building a community of like-minded people who are committed to making the educational experience better for every veterinary professional.

It’s a tall order with a long way to go, but my writing is meant to help push us in that direction. Sometimes my writing isn’t about that at all, but is more about something that I just need to get out into the world. It might be my way of trying to make sense of something, like being fired, or it might be because I’m frustrated by something, such as people’s critique of Descartes (more on that in another post).

In any case, writing and riding are my coping strategies. They help me make sense of the world. And if you’ve gotten this far, then maybe my writing helps you make sense of your world too.

Thanks for reading.